The European Union is poised to impose a ban on imports of Russia’s diamonds — cutting off the world’s biggest diamond producer from one of its key markets.

“Russian diamonds are not forever,” European Council President Charles Michel said on the sidelines of the G7 summit in Hiroshima, Japan, on Friday.

A plan to sanction the Russian industry, worth $4 billion in exports, could be unveiled as soon as this weekend, a senior EU official told journalists during a briefing on Thursday.

Russia produces around a third of the world’s diamonds, and is the single biggest exporter, according to the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), which represents the world’s biggest diamond trading hub in Belgium.

The EU ban would come as part of an 11th package of sanctions over Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and more than a year after the United States prohibited its companies from buying Russian diamonds for non-industrial purposes.

On Friday, the United Kingdom also announced it would ban imports of Moscow’s diamonds later this year, as well as all imports of copper, aluminum and nickel of Russian origin.

The EU ban will affect Russia’s finances, as well as European retailers and traders of diamonds. Buyers of luxury jewelry and watches may also feel the impact in their wallets.

Russia’s diamond exports generated about $4 billion in 2021, according to the UK government. The value of total Russian goods exports that year was $494 billion, according to the country’s central bank. Oil and gas accounted for about half that figure.

The country’s diamond industry already took a big hit in April 2022, when the United States banned imports from Alrosa, a Russian state-owned mining company responsible for 90% of Russia’s diamond mining capacity.

The United States accounts for half of global demand for diamonds used in jewelry, said Paul Zimnisky, an independent diamond industry analyst, while Europe and the United Kingdom together represent only around 5% of the market.

A ban on Russian diamonds could inflate prices for European consumers, especially if diamond production elsewhere doesn’t ramp up.

“It costs billions to produce more diamonds, and it takes up to two years before that production really can be seen in the market,” Tom Neys, a spokesperson for the AWDC, told CNN.

He noted that demand for diamond jewelry was currently “sluggish,” but “the closer we come to the end of the year [when demand tends to pick up]… you will feel that squeeze, and that will probably translate into higher prices.”

The use of diamonds in industry is unlikely to face severe disruption, according to Zimnisky, because more than 90% of those gems are made synthetically in China. Diamonds’ hardness makes them useful in the manufacture of drills and surgical equipment, for example.

It’s possible that synthetically made diamonds could also help fill the gap in the jewelry market left by Moscow’s exports, Zimnisky said, though a glut of cheaper, lab-grown diamonds are unlikely to compete with their natural alternatives. Those will always be a “luxury product,” Zimnisky said.

Europe’s diamond traders are dismayed at the prospect of sanctions.

“We are so against sanctions,” Neys of the AWDC said, adding that traders would simply move their business out of Antwerp in response.

The Belgian city has already “lost a lot of business to Dubai” over the past 15 years, he said, as Antwerp has tightened its rules on transparency and the ethical sourcing of diamonds.

About $40 billion worth of diamonds are moved through Antwerp every year, according to the AWDC. Between 5% and 10% of those diamonds are Russian in origin, down from about a quarter before the war.

Companies are likely to move to the most active trading hub, Neys said. And “when the big ones move, the little ones will follow, and then you are left with nothing,” he added.

Some of the world’s major jewelery makers, including Pandora — the world’s biggest — have already shunned Moscow’s diamonds voluntarily following the invasion.

Other big-name jewelers have also rejigged their supply chains, said Zimnisky, so a ban on Russian diamonds will be felt most keenly by Europe’s small, independent jewelers.

“Ultimately [there’s] going to be a bifurcation in the diamond market… the non-Russian diamonds are going to be routed to the Western world,” he said, while Russian diamonds are likely to end up in China, India and the Middle East.

The biggest task facing Europe is how to design an air-tight ban that prevents Russian diamonds from arriving in the bloc through circuitous routes.

Speaking to journalists on Thursday, a senior EU official said the “main focus” of the bloc’s new sanctions package was “circumvention.”

Zimnisky explained: “If you are, say, a US industry participant… buying diamonds from an Indian cutter and polisher, technically you could still buy Russian-origin stones.”

About 90% of the world’s uncut diamonds are sent to India for cutting and polishing before being reexported to jewelry makers.

That is where the current US ban falls short, according to Neys. “There are a lot of Russian diamonds that still get sold within the American economy,” he said.

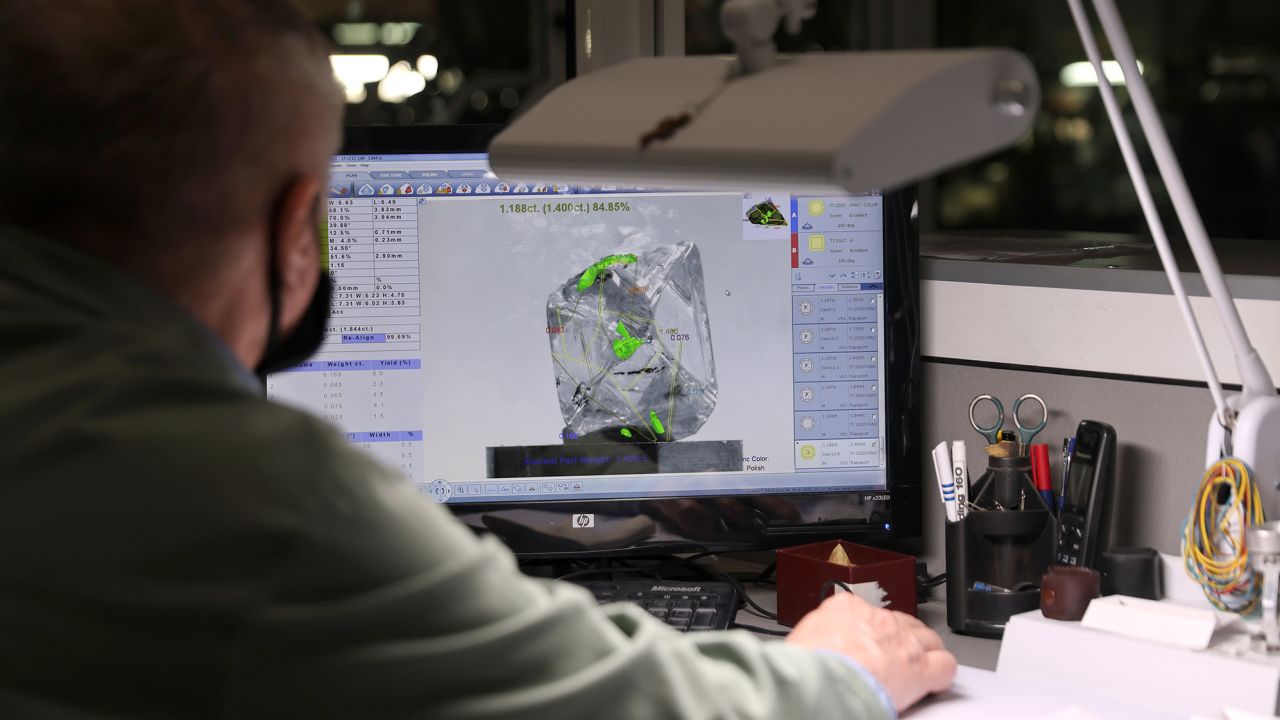

“If you really want to close loopholes, you need to find a system that prevents [Russian] diamonds going to the G7 market,” Neys said. To make this work, he added, jewelers and traders would need access to technology that could determine the origin of diamonds.

— Jake Kwon, James Frater and Niamh Kennedy contributed reporting.

Read the full article here